COVID and pets

Shock for Pets

COVID-19 has become a shock to the whole world, a much bigger shock than many military conflicts and disasters. This epidemic has affected almost every person, almost every family, whether indirectly or directly. The work of the pharmaceutical industry, the logistics of supply and the range of medicines in conventional and online pharmacies have changed significantly.

As you already know, we sell medicines for animals. Among them are such popular drugs as Vetmedin and Carodyl used by owners of cats, dogs and other pets such as rodents. The situation with COVID has also affected them – our four-legged friends have experienced many of the consequences of the pandemic, which we will talk about in this article.

A Look Back

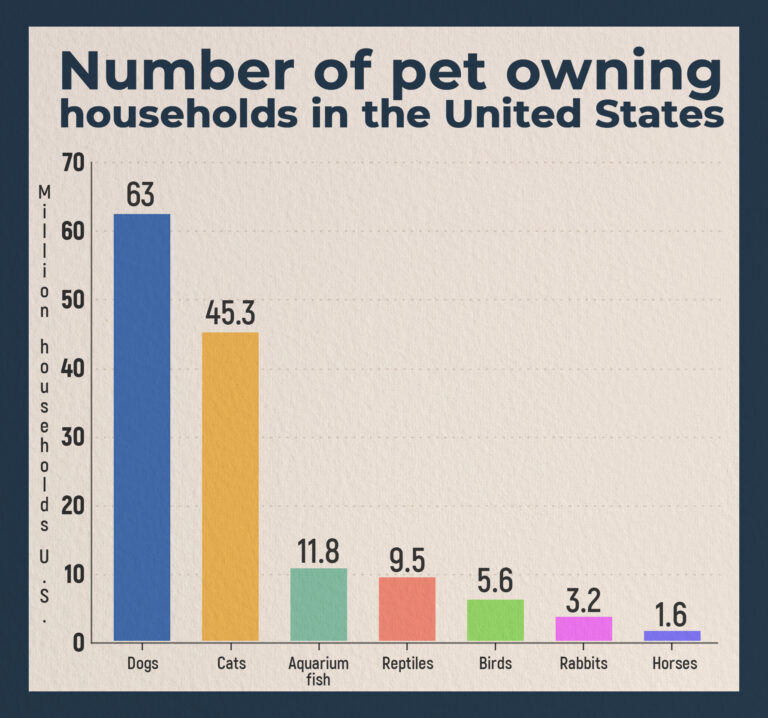

The United States is one of the leading countries in terms of the number of pets owned by the population. No wonder the peculiar cliché about the embodiment of the American place is a private house on a well-groomed lawn, on which a golden retriever frolics. A recent statistical study showed that dogs are the most popular pets among both American families and single people. In the US, more than 63 million households own dogs. The next most popular pets are cats and freshwater aquarium fish (45.3 and 11.8 million households, respectively). Very few people keep salt water fish as pets, as it is extremely difficult to provide them with the proper level of salinity. Only very wealthy and enthusiastic people can afford this pleasure. After aquarium fish, in descending order of popularity, Americans keep reptiles, birds, and rabbits at home.

Of the large pets, horses are the least popular - in large part because, even for rural areas, this animal is very difficult to care for. About 1.6 million households own horses. They are preferred mainly by those residents of rural areas whose work is related to agriculture, for example, farmers.

As of 2020, about 72% of American households owned one or more pets. The last three decades have seen a gradual but steady increase in the number of pets in households. In 1988, the penetration rate of pets into households was 14 percent lower than it is today. Even back in 2018, statistics showed that 61% of US households had pets. So during the years of the pandemic, Americans made sure that there was always someone other than them in the house. In 2018, 33 percent of households had a dog as a pet, 14 percent of households had both dogs and cats under the same roof, and 11 percent of households had only cats. The American Veterinary Medical Association estimates that four percent of households had other combinations of pets, including cats and songbirds in the same household.

New Post-Covid Reality

Virtually every industry has been affected by the COVID-19 pandemic, and the pet industry is no exception. Despite the fact that a significant number of Americans have experienced a decline in income and general levels of well-being, even lost their jobs or were forced to quickly retrain, acquire new skills and explore new professional horizons in order to stay afloat, there was an unexpected effect. An increasing number of Americans began to acquire pets. The number of people who bought a pet for the first time, as well as those who decided that there were not enough pets at home, and bought or adopted one or more animals from a shelter, has increased.

In February 2022, a survey was conducted that showed that 14% of US respondents acquired a new pet in that month. This is four percent more than in December 2020, when a similar survey showed that 10 percent of respondents got a new pet.

Movement restrictions and lockdowns introduced with the beginning of the pandemic forced Americans to spend most of their time at home and abandon habitual activities such as visiting friends, parties, going to the theater, cinema, clubs, cafes, concerts and exhibitions, even the usual gyms and jogging in parks.

A 2020 survey found that roughly 70 percent of Americans of all generations are spending more time with their pets due to social distancing rules. If earlier pets in a large family were cared for mainly by the elderly, while young people and children were busy at work and school, with the advent of COVID-19, the situation has changed radically. Representatives of the younger generations began to pay much more attention to their pets, especially since walking with dogs, for example, during strict lockdowns, has become almost the only way to legally be outdoors. Time has shown that a long stay in four walls is brightened up by our loving pets much better than by endless gadgets.

The other side of the coin is that the pandemic has had a severe negative economic impact on millions of people who have had to deal with precarious work situations. Someone lost their job, someone faced difficulties in switching to a non-remote work format, someone switched to part-time work, someone began to master fundamentally new areas of knowledge in order to be able to earn a living. Financial difficulties, disruption of the usual supply chains and production processes have led to the fact that many pet owners began to worry about the availability of food and products for their pets. While Gen Z and Millennials in the US have often been chided for being callous, compared to the more conservative Baby Boomers, young adults have been significantly more concerned about spending on pets during the coronavirus pandemic. They were especially worried about the procedure for applying for veterinary care. When almost all veterinary clinics were closed in a number of states because of the lockdown, this caused a wide public outcry and indignation, mainly among people under the age of 35.

Pets’ Health

In addition to indirect problems, such as an increase in the cost of feed and difficulties in providing routine veterinary care, Covid-19 has directly affected the health of pets. For example, cats and dogs, and even the much less common hamsters and ferrets, have contracted the coronavirus from their owners. In some cases, this was confirmed by testati, while in others, one had only to guess about the nature of the pet's ailment. Test systems for coronavirus for animals are not widely distributed outside of serious veterinary clinics in large cities, so many animals affected by coronavirus have not received adequate treatment. Many animals devoted to their owners died.

The infection also spread widely among animals in shelters, where the large crowding of animals in a small area acted as an aggravating factor. The coronavirus pandemic has not bypassed both livestock farms and zoos.

Studies have shown that about half of pets caught the infection from their infected owners, with the risk of infection being higher in neutered animals and in those that the owners allowed into their bed. Pets are much less likely to get infected from humans than humans are to get infected from other humans.

So far, throughout the existence of COVID-19, scientists have found no evidence that infected pets can transmit the virus to humans. Although the fact that cats and dogs can become infected from their own relatives is already a proven fact. Moreover, if the animal has strong immunity, it may not show any signs of the disease. Cats can transmit the virus to other animal species, such as white-footed hamsters, but people may not be afraid of getting infected from their pets. This is also supported by empirical observations.

COVID-19 still hasn't left the global stage. It is possible that in the near future the United States will have to face a new wave of this disease, for which now we are all incomparably more prepared than when the pandemic was just beginning. We are armed with vaccines and effective treatments to reduce Covid deaths and the risk of severe complications many times over. However, if you find yourself in an area where there is a surge in the incidence of COVID-19 and get sick, then as part of the prevention it is better not to let your pets go for walks so that they don’t infect other pets. Of course, this mainly applies to dogs. In addition, if a person is confirmed to have COVID-19, it is advisable that he maintain social distance not only with other people, but also with his pets. Of course, this option is only suitable if you have any relatives who are ready to take care of your pet.

Knowledge about the clinical manifestations of the disease in animals is limited, and mainly because the pandemic, which is avalanche-like in nature and disrupted the entire habitual way of life of entire countries, if not continents. As a result, targeted veterinary research related to COVID-19 has not been conducted or has not been sufficiently extensive. However, current clinical and statistical data suggest that clinical signs of COVID-19 in dogs and cats may include, but are not limited to, cough, sneezing, shortness of breath, nasal discharge, eye discharge, vomiting or diarrhea, fever, and lethargy. As in humans, asymptomatic infections can also occur.

Pets against Psychological Issues during the COVID-19 Pandemic

Pets have played a huge role during the coronavirus pandemic, literally saving people during social isolation. During the strict coronavirus restrictions, the arrival of a new pet or devoting a lot of time to caring for an existing one has become an effective psychological relief for millions of Americans. There has also been a sharp increase in the number of applications to shelters where homeless animals are kept: in 2020 there were 13% more of them than in 2018. It is curious at the same time that cats turned out to be more in demand. According to the founder and director of the Bissell Pet Foundation, an organization that provides assistance to animal shelters across the US, approximately the same number of dogs and cats were adopted from shelters before the pandemic. However, during the pandemic, more cats were adopted from shelters than dogs. This is partly due to the fact that a cat is easier to have as a first pet, partly because it is a more “cozy” animal that brings warmth and calmness to the house than a dog that pulls the owner outside. In addition, not all people are mobile enough to walk the dog for a long time. Caring for a dog is more difficult, and the walk routine subjugates the rhythm of the owner’s life.

The COVID-19 pandemic has caused a sharp spike in exacerbations of mental disorders, as well as the prevalence of ordinary stress and anxiety. The level of anxiety has grown due to uncertainty and awareness of the potential threat to life, material well-being, freedom of choice - all that we used to take for granted and no longer appreciate. Simply put, anxiety is the fear of losing control. Therefore, in order to improve the quality of life in conditions of isolation, people first of all needed to determine what was within their control zone, what they could manage. For example, observing hygiene measures, reducing social contacts, ventilating the room, following the recommendations of doctors so as not to endanger yourself and others - all this helped to increase the feeling of control over your life. It is also useful for psychological health to take care of the well-being of yourself and loved ones, as well as your pets. Communication with pets helps to reduce feelings of loneliness and stress due to the unconditional love, support and psychological help received from a pet.

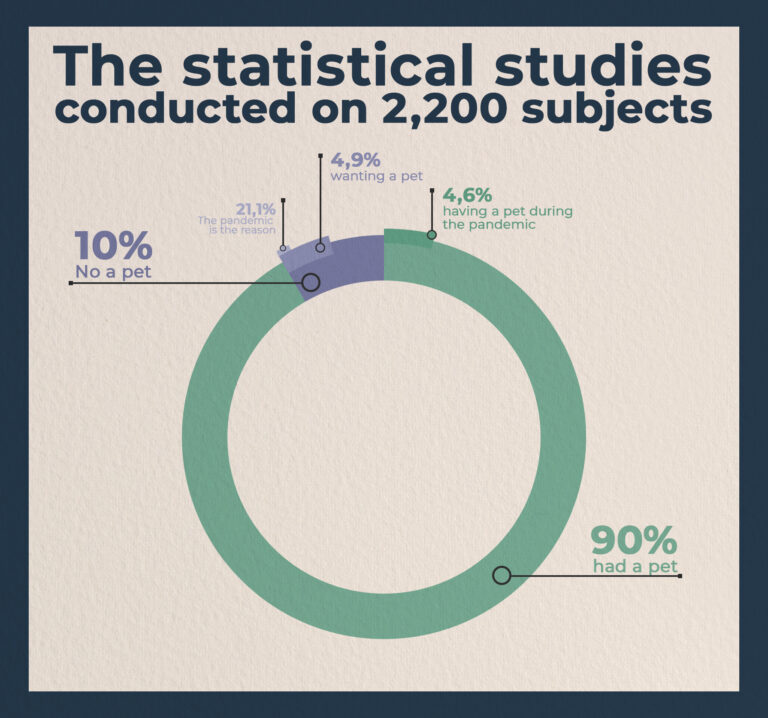

Notable is one of the statistical studies conducted on 2,200 subjects, residents of different states of the United States, who were in isolation during the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic. 90% of the participants had a pet, with 4.6 percent of those having a pet during the pandemic. For 6 percent of respondents, pets acted as guides. Among participants who did not own a pet, almost half (48.7 percent) reported wanting a pet. Of those who want to get a pet, 21.1 percent of people made this decision precisely because of the restrictions that came during the pandemic. At the same time, scientists wrote that too high rates of intimacy of relationships with animals are associated with low estimates of mental well-being before the introduction of social distancing measures.

It is generally accepted that the presence of animals is good for human health, and this belief may have contributed to the increased interest in pet ownership and demand for pet adoption seen in the US during the COVID-19 pandemic. However, the scientific literature is divided on the relationship between pet ownership and human health and well-being: while some studies have confirmed the existence of a positive association, others have found null associations or found a negative association. However, it can be concluded that for most people owning a pet can be more or less beneficial during times of high stress.

Animals and COVID-19 Origin

Notably, current evidence suggests that the SARS-CoV-2 virus that causes the disease known as COVID-19 originated from an animal source, but that source has not yet been identified. Disputes about what kind of animal was the original carrier of this disease are still not hatihli and are being conducted at the highest level. It is reliably known that the pandemic develops through the transmission of the virus from person to person by airborne droplets as a result of coughing, sneezing and talking. Genetic sequencing data show that the SARS-CoV-2 virus is genetically closely related to other coronaviruses circulating in populations of bats of the genus Rhinolophus (horseshoe bats). However, there is still insufficient scientific evidence to identify the source of the mutation that gave rise to SARS-CoV-2, or to explain the original route of its transmission to humans. There are suggestions that this pathway could involve an intermediate host.

Results from experimental challenge studies suggest that poultry and pigs are immune to COVID-19.

Clinical signs of COVOD-19 in Animals

A study of typical histopathological features of COVID-19 in domestic rodents, mainly mice, showed that these features included interstitial pneumonia with significant inflammatory cell infiltrate around the bronchioles and blood vessels, and viral antigens were detected in bronchial and alveolar epithelial cells. These pathological changes were not observed in wild-type mice infected with coronavirus. In Syrian hamsters, histopathological changes were recorded in the respiratory tract and in the spleen. Notably, some people who are severely ill with COVID-19 also have inflammation and enlargement of the spleen. Presumably, this is due to the fact that the spleen is activated as one of the organs whose task is to give an immune response to a severe disease.

Rhesus monkeys infected with coronavirus in most cases showed lesions similar to those seen in humans. Cats infected with coronavirus showed massive lesions in the epithelium of the nasal cavity and trachea, as well as in the lungs.

In the case of domestic ferrets, there were no severe clinical manifestations, but serious pathological changes were observed, such as severe lymphoplasmacytic perivasculitis and vasculitis, an increase in the number of type 2 pneumocytes, macrophages and neurophils in the interalveolar septa and in the cavity of the alveoli, as well as moderate peribronchitis in the lungs.